The Alte Dombach paper mill historic site (Bergisch Gladbach)

Another guest post from Jürgen Wegner of Sydney (Australia), and occasionally Europe, in his series of museum portraits. Originally published in The book ark, 94 (April 2018), p. [14-17].

The paper industry is perhaps no less important today and historically than the printing industry. For some reason, it is far less apparent, seems far less studied and, generally, much less known than printing. There are historical societies and associations, special collections and libraries, the occasional exhibition, workshops and courses as well as museums (or sections in larger museums). But, given the importance of paper and papermaking to society and the development of culture in general, paper and paper history is a relatively neglected area of human achievement, industry, invention, commerce… even art. No less so in Australia and New Zealand where paper and papermaking have their very own and very long history. Indeed, until quite recently, papermaking was one of Australia’s and New Zealand’s major manufacturing industries. While there are plenty of printing museums around—albeit of a basic nature—paper has gone almost without a single presence.

This is no different overseas where there are paper museums but these are few and far between by comparison. Perhaps it is due to the fact that, unlike your corner printing shop, manufacturing required machinery and complexes on an epic scale. Hard for your local authority to embark upon and maintain. So, paper museums tend to be of the old, historic paper mill type such as the Papiermühle Homburg which I visited a few years ago, and which you would need a car to visit.

Unlike the industrial complex now a paper mill museum at Bergisch Gladbach, the Papiermühle Alte Dombach which is just a short suburban train journey from Köln.

When I mention Bergisch Gladbach, the world-famous Zanders[1] paper mill will immediately spring to mind. (And Zanders was the first paper mill I ever visited). Bergisch Gladbach is one of those small German towns most notable for their tidiness and respectability (the Protestant north). What is unusual is that when you get off the train, you are virtually almost opposite the large Zanders industrial complex. No doubt as rail access is a key factor in the distribution of paper. Also unusual are the platforms themselves. You get off the train and there are no barriers, guard rails, warning signs, three-metre high fences with razor wire. You just get off and there you are. Here such railway stations would be our OHS nightmare. People could fall—or throw themselves—in front of trains. They might pick up a seat and throw it in front of a train. And, heaven forbid, one might even have travelled without a valid ticket!! None of these things seem to be an issue there and I guess it is just foreigners like myself who wonder at the civilization of it all.

I asked for directions and they thought I was mad. But, in fact, the Papiermühle Alte Dombach is only a shortish but very pleasant walk from the station—even in the rain (and this was the only day that it rained the whole time). Especially if you take the walking and cycling path along the stream which passes on through the museum site, the Strunder Bach. The attitude of people in Germany to industry and technology is quite different to that here. I have a brochure from the Freundeskreis Technoseum (Friends of the Technoseum) in Mannheim which is titled: ‘Nothing is more exciting than technology’. The Papiermühle Alte Dombach is part of the state of North Rhine Westphalia’s (the equivalent to a New South Wales or Victoria) LVR-Industriemuseum, a museum made up of seven individual museums which have preserved the industrial and technological past of the state. The museums include a tin plating factory, an ironworks, a power station, a textile factory and a spinning factory as well as this paper mill historic site.

Paper was first made in the Alte Dombach as early as 1614, though the earliest papermaking here dates from 1582 with Bergisch Gladbach the site of twenty papermills. Papermaking originally was a small affair and the history of the site is the development of paper mills from small family affairs to large commercial industrial sites. Both the Alte and the Neue Dombach sites were bought up by Zanders in 1876. The old area was closed in 1900 though workers cottages remained with the new site also closing in 1930. In 1987 the site was gifted to the LVR, the Landschaftsverband Rheinland (Rhenisch Countryside Association), which opened it as an historic industrial complex in 1999.

The Papiermühle Alte Dombach historic site is made up of two general sections. The main series of buildings is near the entrance and comprises a large multi-storied building housing the permanent displays with external water wheel, a drying house with offices, the museum shop and rooms for special exhibitions, a workers’ cottage which is also a small café and restaurant as well as stables and a workshop. At the other end, there is the old paper machine hall with the 1889 paper machine restored to the site. Between the two there is an open-air machinery display of items used in the preparation of the raw materials.

First of all, a note on the special exhibition. There are regular temporary exhibitions which are used to show visitors some of the more unusual aspects of paper and papermaking. The exhibition at the time was called Kleidung, Smart phone und Bananen aus Papier (Clothing, Smartphones and Bananas made from Paper). The Chinese have a tradition of burning objects which the deceased might find useful in the next life. Objects they may have used but equally objects which they would have liked to have had in this life but now will have in the next. Expensive objects and luxury items. The tradition is a means whereby those who are left behind show their love for the deceased.

Now I have known about the fake money for a long time—there is even a collection of this material on file here. But the extent, size and complexity of this reproduction finery has to be seen to be believed. And can run to quite a considerable amount of money in its own right. There were the inevitable packets of cigarettes in perfect replica but, for legal reasons I imagine, produced with slight typos—Lucky strlke, Danhill and Marlbero packets were on display. There were complete replicas of laptops and mobile phones, a Rolex (costs €30), miniature villas, a motor-bike as well as a bicycle (with turning wheels)—all made of paper. As well as packets and packets of banknotes—from the Hell Bank. The latter of interest because they mostly seemed to show smiling portraits of Mao Tse-tung and brigades of equally smiling young peasant workers.

The main museum complex is in the old paper mill building which also functioned as a drying loft. The displays take you from general discussion topics such as the world’s consumption of paper and paper products, especially advertising and packaging, the kinds of papers made, paper machinery and equipment, processes including paper testing, the paper trade. Rather than provide a resumé of the museum guide, a few of the personal highlights:

- ‘The world is made of paper’—so the title of an exhibition on printed ephemera that was held at the Universität Göttingen some years ago. One of the most fascinating items on display was an album of historic printed paper bags from the days when you bought coffee as beans loose in special pre-printed bags. From about 1900 judging by the stunning Jugendstil designs of some of these bags.

- There were also some items of the heavy machinery—or parts of heavy machinery—used in the production processes on display. One of these was a restored stamping battery, a part of the unit used to grind wood into pulp as well as a very ancient Hollander.

- But also, a very modern, smaller one used to prepare the stuff for the hands-on paper making displays.

- These were of two kinds. The first is a display of traditional papermaking using paper moulds and a vat. As part of the display, visitors are encouraged to make their own sheets of paper using traditional means. Also, several times a day, a demonstration of papermaking on a ‘proper’ paper machine, albeit a scale model one—a baby at only five metres. This Laborpapiermaschine or laboratory paper machine was manufactured by the Papierfabrik GmbH in 1957 and was the gift of the Bayer AG. These were used for paper testing but are to all intents and purposes exact smaller versions to the large ones. This one was used by Bayer to test the properties of various dies used in the papermaking process. At the end of each session, examples of the papers made by the two processes were given out. Examples of watermarked paper can also be bought at the museum shop.

- Perhaps the most unique—and bizarre—display is that of specimens of hygienic papers, i.e. toilet paper. The display room is small as in modelled on the home bathroom toilet. One wall has a display of 64 different kinds of toilet papers (each labelled). The opposite wall shows a short film on the history of the toilet and toilet paper. To activate a session, visitors have to sit down on one of the two toilets provided—sit down on their lids, that is—which then activates the film.

- A personal highlight were the several large and detailed displays of paper trade grey literature. Some of these also date from around 1900 and the paper sample swatches, for example, designed and produced at this time, are of the most exquisite graphic design. Other displays include a large paper sample box from J.C. Kayser & Co. (Dresden) as well as large, substantial sample books—they look like the Brockhaus—of sample papers and boards from Freytag & Petersen (Leipzig).

- One room showed an almost infinite variety of historic paper testing equipment. After all, modern commercial papermaking is a highly complex and sophisticated process which requires testing and record keeping at every stage.

- A large amount of advertising as well as historic packaging is also displayed.

Highly educational and informative. But it was the outdoor machinery ‘sculpture garden’ as well as the original Neue Dombach machine hall which were personally of greater interest. On the way to the latter you pass a hedged-off area in which are displayed some of the larger industrial pieces of machinery and equipment. Here there is another very large wood grinder, a digester and a Hollander with two very large crushing wheels (1888).

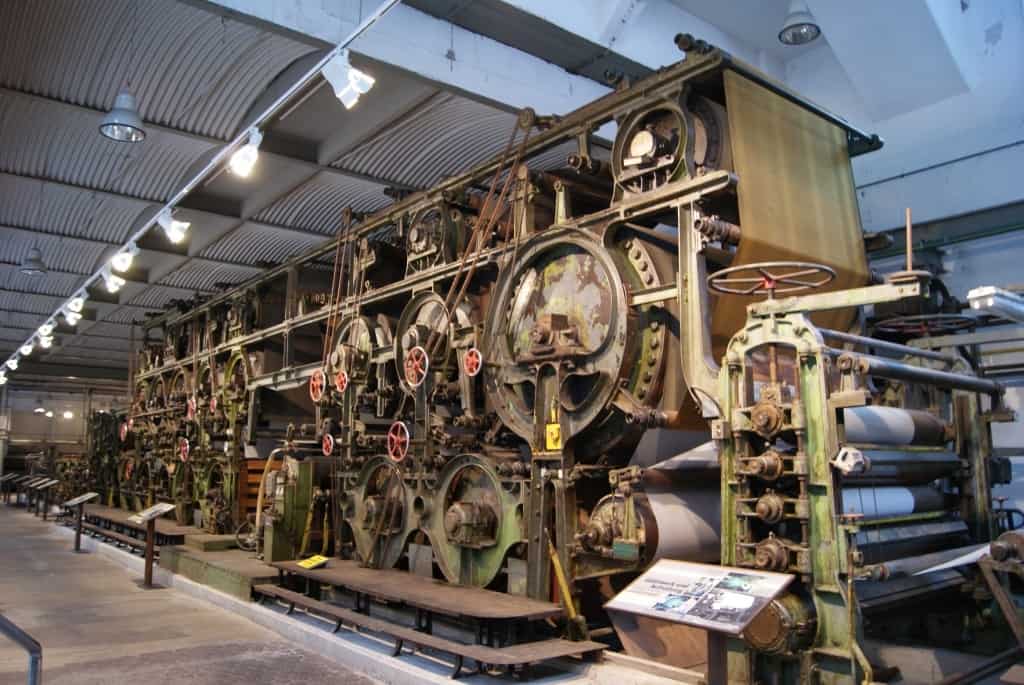

A little further along, the PM4 or the paper machine hall no. 4. This fine old building was constructed around 1913 and still houses the ‘original’ paper machine from 1889. Now paper machines are large and expensive items of machinery—this one is forty metres long and some five metres high. You don’t just trade these in for this year’s model. And so most paper machines tend to get modernized, added to, improved. And can have a very long life indeed. This one made it to over a hundred years continuing to operate at the Zanders Gohrsmühle city site until 1991. It was gifted to the museum in 1993. Few people will have had the privilege of having had a guided tour of a paper mill—I am fortunate in having had four—and for visitors to see this full-sized paper machine helps to put papermaking and paper in a better perspective.

The hall also includes a number of other paper machines—smaller ones but of great beauty. And photogenic. I must admit that I took a great many photographs of the machines as well as the detail. Two of these came to the museum in 1990 after the collapse of the German Democratic Republic. One is a round cylinder paper machine for making cardboard—a smaller machine being more economical that one of the large continuous web paper machines. The second is a machine from 1910 with brushes for coating paper with a variety of coatings and pigments, especially for the production of photographic paper.

The museum shop used to have quite a good selection of books on paper history (which I all bought) though it is a general visitors shop. There seem to be few and fewer things for the specialist and, as everywhere, things must address mass popularity. But good to see that a whole series of about ten postcards on the museum and various processes is available—for the few who still send postcards, that is! When was the last time you saw any souvenir postcards on the subject of printing, paper and type manufacture in any museum?! Out in the park there is also an outdoor sculpture in the form of a large globe showing the major paper consuming countries of the world. Australia is there—but there is no Tasmania on the map—one of Australia’s greatest paper producing states though perhaps because their paper consumption is negligible. And while New Zealand is there to be seen on the globe, no data as to New Zealand’s paper consumption either.

A short video on the Papiermühle Alte Dombach is available on their website. As is a short virtual tour as well as a history of the museum.

Jürgen Wegner

Librarian, Sydney, 2018.

Rheinisches Industriemuseum Alte Dombach

51465 Bergisch Gladbach, Germany

info@kulturinfo-rheinland.de

+49 (0)2202 93 668-23 and 93 668-0; fax: +49 (0)2202 93 668-21

https://industriemuseum.lvr.de/de/die_museen/bergisch_gladbach/schauplatz_3/papiermuehle_alte_dombach.html

[1] https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zanders_Papierfabrik