How print became heritage:

150 years of printing museums

Alan Marshall, chair AEPM

Text of a paper given by Alan Marshall at the conference of the Association of European Printing Museums, Making history: collections, collectors and the cultural role of printing museums, Museum of Typography, Chania, (Crete, Greece), 11-14 May 2017.

How did the eminently practical activity of printing come to be thought of as a legitimate object for conservation, study and mediation by heritage specialists? Or to put it another way, how did print leave the workshop and find its way into the museum?

A process camera recently installed in the permanent display of the Nederlands Steendruckmuseum, Valkenswaard, The Ntherlands. (Photo: AM)

Our starting point is of course the book, which from earliest times has often been considered to be an object of value because of its symbolic and intellectual content. As such, it was an object to be preserved and transmitted from one generation to the next. But it was only in the course of the 19th century that printed products and, more specifically, the tools and techniques of printing, came to be looked upon as a form of cultural heritage in something like the modern sense of the term.

The outline which follows offers a brief account of where printing museums have come from and how they have evolved how, since the middle of the 19th century, printing and more recently graphic communication have become part of our cultural heritage.

A quick overview of this gradual process suggests that the development of printing as heritage has followed the diversification of the forms and uses of printed products which began with books and prints, continued with the periodical press, later with the multitude of administrative and commercial uses of print, and which continues today with what we now call graphic communication, a domain which goes far beyond that of traditional printing, but which is its natural extension.

In other words, the field of what is generally considered to be printing heritage has been gradually expanding since the middle of the 19th century.

Over the years, the progressive enlargement of the field of graphic heritage has expressed itself through the establishment of institutions and other organisations dedicated to the preservation, the study and the exhibition of artefacts related to printing and printed products. Among these various structures, we naturally find printing museums. But we also find libraries, archives, special collections, heritage workshops, a wide variety of museums who happen to find themselves with print-related objects in their collections.

This network of heritage organisations is in turn founded upon an ensemble of scientific disciplines which determine how the history of printing is written and narrated in museums: scientific disciplines which are an essential part of the process by which the perimeter of graphic heritage is defined and legitimised.

If we were to make a list of these disciplines in a more or less chronological order of their development, it would include:

- the history of printing, from earliest times – and still often today – written by printers themselves,

- bibliography: which concerns itself principally with the book and which would lay the foundations for a more recent discipline: book history,

- the history of art: which originally concerned itself with prints and printmaking, book illustration and decoration, and artists’ posters,

- the history of typography: which was originally pursued by practising printers and bibliographers,

- the history of the newspaper: a field which is largely dominated by political and social historians,

- the history of graphic design: which developed in the course of the second half of the 20th

More recent disciplines would include:

- the history of communication: which for a long time considered print largely as a simple preamble to ‘modern’ communications,

- and most recently of all, we would find information history: which, crossed with the history of libraries and the history of computing, today lays claim to a vast field which includes the graphic industries.

In the light of the institutions and disciplines of graphic heritage, what have been the main stages in what specialists call the ‘heritagization’ of graphic communication?

If we look at the foundation dates of printing museums we can identify four periods:

- the first covers a large part of the 19th century: this was the time of the precursors and pioneers,

- the second period covers the first half of the 20th century, and was, above all, a time of consolidation and diversification of collections,

- the third period – just after the Second World War – tended to celebrate the heritage of Gutenberg in a changing world,

- the fourth period, starting in the 1980s, has been largely dominated by the preservation of the memory of techniques and trades which were fast disappearing under the onslaught of electronics and computers.

This periodisation – necessarily approximate and somewhat arbitrary – is based on the census of printing museum foundation dates which the AEPM is currently compiling, which includes about 130 museums to date.

The first period – that of the precursors and pioneers – covers a large part of the 19th century.

During the first half of the century, the principal category of printing heritage – the book – was confined to private collections and libraries, access to which was limited to their owners and to a small circle of connoisseurs. Exhibitions of books were largely inexistent at that time. The first places where printed products were offered on display, in the form of books and prints, were private cabinets of curiosities, and the first so-called ‘public’ museums (access to which was, in reality, generally very limited). In such places books and prints were displayed, above all, in order to illustrate points of history, scientific discoveries, historical monuments and topographical features, or illustrious figures of the past.

One of the very first museums in which books were displayed as books – that is to say for their inherent qualities –was the Meermanno Museum which was founded in The Hague in 1852, thanks to a rich bibliophile who gave his collection (and a mansion in which to house it) to his native city in order that it be accessible to as large a public as possible.

The closing decades of the 19th century saw the creation of other museums related to printing: the Plantin-Moretus Museum in Antwerp in 1877; the Gutenberg Museum in Mainz in 1900; the Enschedé Museum in Haarlem four years later; and the Musée du livre in Brussels in 1906. In these museums, the tools and techniques of printing also began to be displayed alongside the book, which nevertheless remained the main focus of the displays.

These first book and printing museums were set up in a favourable economic context: the Industrial Revolution was in full spate, and printing reigned supreme as the foremost means of communication. What better time to celebrate and legitimise the first mass media in history?

The history of the book and of printing also contributed to the construction of national identity and prestige, by way of celebrations and commemorations of major inventions and important personalities such as Coster, Gutenberg, Caxton and Senefelder, commemorations in which political, religious and social considerations were never very far.

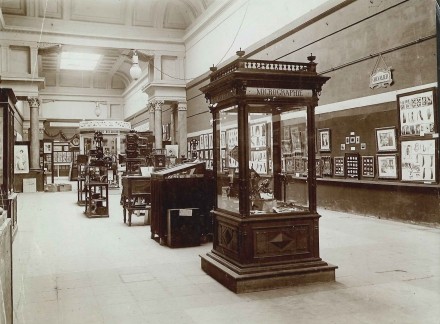

The 19th century was also marked by the great national and international expositions, aimed at showing the industrial and cultural prowess of the host nation to its best advantage. The graphic industries – papermaking, printing and publishing – at the cutting edge of communication technology, were systematically present at such events, displaying their technological and artistic achievements, and often taking advantage of the occasion to include a ‘retrospective’ section displaying the most prestigious examples of printing from previous centuries.

At the beginning of the 19th century, interest in rare books and fine printing was confined to a small circle of connoisseurs and collectors. In the course of the century, however, interest in rare books began to spread as the result of the creation of public libraries, of the various commemorations which have already been mentioned, of the first temporary exhibitions of rare books, and of the growth of the bibliophile market, which was encouraged by a new generation of publications aimed at the general public and dedicated to book collecting.

As for the study of rare books, it too developed new methods, often with a view to resolving the problems which arose when trying to identify incunabula, or other important publications such as, notably, the first editions of the works of Shakespeare. The resulting discipline – bibliography – relied initially on close study of the typography and modes of production of 15th and 16th century books. Towards the end of the century, it opened up to more social aspects of the production, distribution and consumption of the book.

While bibliography was making a decisive contribution to the development, first of printing history and, later, of book history, art history was concerning itself principally with aesthetic aspects of certain selected sectors of print production, such as engraving and etching, book illustration, decorated bookbindings and illumination and, as of the closing years of the century, illustrated lithographic posters produced by artists.

The second period in the heritagization of graphic communication covers the first half of the 20th century, a period of consolidation and diversification of graphic heritage collections. The period saw the creation of a certain number of museums, but these were for the most part in the early years of the century – which were, coincidentally, the golden age of printing – a period of rapid growth and far reaching innovation, both in technical terms, and in terms of the forms and uses of printed products. Print markets were diversifying rapidly, as were modes of production and distribution.

These changes were driven by several factors: the need for a growing variety of administrative documents in an ever more complex society; industrial and managerial capitalism’s insatiable need for commercial and administrative documents; and the growth of advertising and packaging with the advent of the consumer economy.

The corollary of the diversification of the forms and uses of printed products was the emergence of the graphic designer as an autonomous agent within the production process. (The term graphic designer is of course anachronic.) The emergence of graphic design was concomitant with what we might call the document economy which announced the end of the book as the principal motor of print production and graphic innovation.

In heritage terms, the first manifestation of this shift in the centre of gravity of graphic production away from books was the creation of newspaper museums such as the Persmuseum in Amsterdam in 1902; or the Musée internationale de la presse in Brussels in 1907.

The turn of the century also saw the first temporary exhibitions of illustrated posters which, unlike most printed publicity, quickly became objects of collection, a merchandise whose value was closely linked to the reputation and market rating of the best-known poster artists, many of whom were already present in the art market. It was also at this time that the first museums dedicated to engraved and etched prints appeared.

But from the point of view of the heritagization of graphic communication the first half of the 20th century was above all a period of consolidation and diversification of print-related collections. Collectors were increasingly numerous and, inevitably, a small number of pioneers began to expand the perimeter of their collections to include new types of document, beyond the traditional fields of books and prints. Their collections increasingly extended to the products of jobbing printing – printed ephemera to use today’s terminology – those everyday documents which though generally considered by collectors of the time to be lacking any real interest, were greatly appreciated as sources by social, political and economic historians. Up until the Second World War, printed ephemera was, generally speaking, largely ignored by historians of printing and typography (apart from a few specific categories of collectable documents). Rare were those who considered them essential for any real understanding of the history of graphic communication, and it was only during the 1960s that printed ephemera began to be studied systematically by historians of typography and graphic design.

The third period in this short exploration of the heritagization of print is that of the celebration of Gutenberg’s heritage.

In the wake of the Second World War, the printing industry entered a period of reconstruction and modernisation after several years of war and penury. As a media, print was still predominant, both from an industrial and from a cultural point of view, resisting the encroachments of cinema, radio and television. But storm clouds were beginning to appear on the horizon: photographic type composition, electronics and the still new-fangled computers augured important changes to come; changes whose impact was as yet impossible to discern with any certainty. People were beginning to talk about the end of hot metal. Similarly, the ever more important role played by advertising agencies and graphic designers suggested that the perimeter and organisation of the printing trades were on the move.

During the fifties and sixties the number of new printing and related museums increased significantly. The AEPM census includes 16 museums founded between 1950 and 1975: museums dedicated for the most part to the celebration of print’s glorious past and its most prestigious products. Among the more significant creations of this period we might mention the Klingspor Museum in Offenbach in 1953; the Museo Bodoniano in Parma in 1963; and, a year later, the Musée de l’imprimerie et de la banque (as it was then known) in Lyon.

This period was also one of intense activity on the part of print and book historians with the publication of Fèbvre and Martin’s The coming of the book, one of the founding texts of modern book history, the creation of learned societies like the Printing Historical Society in the United Kingdom, a spate of important works on the history of printing and typography, and the stirring of a serious interest in vernacular design and typography in the form of printed ephemera.

The fourth period in our brief chronology takes us from 1975 to the present day, a period marked by a veritable flood of new museums, many of which were dedicated to preserving the memory of trades and techniques which had already disappeared from the industrial landscape, or which were in the process of disappearing. Within the industry, offset printing had captured a large part of the market by the end of the 1960s, and it was then that the trade began to fully realise that hot metal was on its last legs, and that a generation of printers was in danger of totally disappearing along with their traditional skills and knowledge.

Then, in the 1970s and 1980s, the massive irruption of electronics and computers changed everything. With the advent, in quick succession, of computer typesetting, desktop publishing and digital networks, suddenly it had become vitally urgent to preserve traditional printing techniques and skills. Printing museums began to spring up everywhere: the number of creations increasing fourfold as compared with the previous period, to 88 for the years 1975 to 2010 – according to the (incomplete) AEPM census.

The content of these new museums came from all sorts of sources: from private collections; from printers modernising their equipment or closing down for lack of a successor; or collections put together by former members of the trade. And, as luck would have it, public sources of funding were, generally speaking, conducive at this time to initiatives involving the preservation of both the material and the immaterial culture of trades such as printing.

In parallel with this movement, libraries were becoming increasingly aware of the importance of exhibiting and interpreting their collections of books and other graphic artefacts, an activity which had hitherto been restricted mainly to larger heritage libraries. Archives also – though to a lesser extent – began to develop exhibitions and other forms of mediation in order to bring their collections, often of printed documents, to the attention of a broader public.

On the scientific front, this period was globally positive. In the academic world book history came to be recognised, though not without difficulty, as a legitimate discipline more or less in its own right. Similarly, the history of graphic design made considerable progress, liberating itself partially from the influence of art history thanks to the contribution of teachers and researchers closely involved with the design profession, and who, additionally, helped fill the gap left by the disappearance of the generations of printer-historians which had had such a strong influence on the history of printing and typography up until the 1970s.

As for printing history, however, it fared rather less well than book history during this period. As the literature of the time shows, it was generally less dynamic. The integration of printing within the much broader communication industries encouraged many to think that more or less everything had been said on the subject, an impression which was reinforced by the insistence of researchers in the field of information and communication studies on new audiovisual technologies. Professional training programmes also finally abandoned any last pretence of being interested in the history of graphic production which seemed increasingly irrelevant in the face of the digital revolution and the galloping specialisation which was affecting all aspects of the graphic industries. Paradoxically, just when book history was making its breakthrough, printing history seemed to be quietly disappearing from the scene. As the focus of book history moved from the production and distribution of printed documents to their reception by readers and users, the history of printing found itself increasingly isolated and ignored, particularly with respect to the twentieth century, the historiography of which remains largely virgin territory today.

Since 2010, the rhythm with which new printing and related museums are being set up has slowed significantly. Though budgetary restrictions are no doubt partly to blame, the slow-down is probably also related to various structural problems which printing museums are currently facing: such as the imminent disappearance of the last generation of printers to have practised hot-metal and lithographic techniques in industrial conditions, and the unwritten skills and knowledge of which they were the last repository.

The sustainability of many independent printing museum projects can also be problematic as the first generation of printer-collectors seeks to transmit its collections, skills and knowledge to the following generation.

The preservation of digital artefacts also poses a formidable series of problems in terms of their identification (what should be preserved?), their conservation, and their display and mediation.

To complicate matters further, the success of book history in recent years has not always had a positive impact on printing history, for one of its consequences has been the recruitment of future historians of graphic heritage mainly from the humanities, with the result that the more technical, economic, industrial and properly graphic aspects of printing and printing culture are often overlooked, or even feared, by researchers who have never received any relevant training these aspects of the history of graphic communication in the course of their studies.

On the positive side, however, the exhibition and mediation of books and other printed documents are now firmly anchored in the cultural programmes of libraries, archives and university special collections, as well as in those of an increasingly broad spectrum of museums active in other fields.

The creation of a certain number of museums partly, or entirely, devoted to graphic design is also to be applauded. Unfortunately it does not generally occur to these museums that they may have something in common with the many printing museums, book museums and heritage libraries who have been exhibiting graphic objects for over a century and half. Equally unfortunately, it has to be said that printing museums generally return the feeling: this antagonism – indifference might be more exact – is doubtless a reflexion of the frontiers which traditionally define academic and historical disciplines, with the result that a lot of work remains to be done to convince both camps that they do actually have a great deal in common.

That said, it is worth underlining that throughout Europe a new generation of graphic design historians is gradually finding its voice in the academic world, teachers and researchers who often pursue a professional activity, and who are more or less conscious of the achievements of past generations of printing historians as precursors in the field which we now call ‘material history’, and of the necessity to develop a more open, transdisciplinary approach to the study of graphic communication and printing heritage.

Today, the missions of printing museums and the conditions under which they pursue them are changing. In general terms, the digital revolution is opening up new perspectives for museums of all kinds in practically all fields. More specifically for printing museums, for nearly four decades now digital technologies have been profoundly altering the very nature of their object of study – graphic communication – which now extends far beyond the traditional field of printing.

Similarly, the historical disciplines which underpin the work of printing museums are undergoing a certain reconfiguration. The traditional world of printing history is opening up to new disciplines such as the history of graphic design and the history of information, disciplines which in turn open up new perspectives and offer new tools for understanding the profound changes which graphic communication has undergone in the course of the twentieth century.

In the closely related field of book history, the advances made in recent years in establishing national histories have created the conditions for the pursuit of international comparisons, which will provide us with a fuller understanding of the ways in which the production, distribution and consumption of printed texts and images have influenced every aspect of human activity over the centuries, crossing and re-crossing geographical, political and cultural borders.

The heritage landscape itself is also in the process of changing, and with it the distribution of the missions of the various organisations concerned with graphic communication. New relations are forming between the history of graphic communication and the institutions which have traditionally been responsible for the preservation and transmission of graphic heritage: such as museums, libraries, archives and university special collections, organisations whose missions increasingly overlap in terms of the nature and management of their collections (notably as regards the frontiers between artefacts and archives, always difficult to establish in the field of printing heritage), and thanks to a growing number of interdisciplinary collaborations among heritage and cultural actors.

The opening up of new perspectives for the preservation and mediation of graphic heritage creates new challenges for printing museums who must constantly re-evaluate the nature and perimeter of their collections and the ways in which they are exhibited and interpreted in order to refocus their missions and identify the most relevant and effective means of developing them, of bringing them to the attention of as broad a public as possible, and of transmitting them to future generations.

Alan Marshall