Talk given by Alan Marshall at the conference of the Association of European Printing Museums, Why do people make printing museums, held at the Atelier-Musée de l’imprimerie, Malesherbes, France, 5-7 May 2022.

Why do people make printing museums?

A good question. To which there are probably almost as many answers as there are museums. So rather than address the question directly, I’d like to offer a few thoughts on the context in which people have been making printing museums for the last fifty-odd years. And to do that, I’ll start with a brief overview of the topography of printing museums, before going on to take a look at how some of the disciplines that underpin the work of printing museums have changed since the 1970s.

Let’s first of all take a quick look at the topography of printing museums.

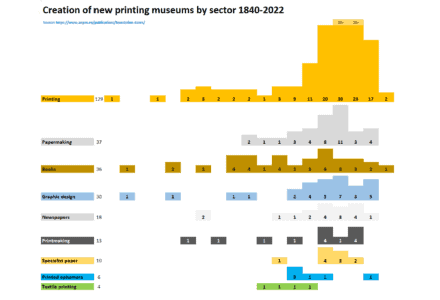

Here we have a table showing the numbers of museums that have been created in the field of graphic heritage since the middle of the 19th century. The figures are based on the timeline of print-related museums which can be found on the website of the AEPM. Because the compilation of the timeline is ongoing, the data is necessarily incomplete and so is given simply as an indication.

The first thing we see is that people have been making printing museums for over a hundred and fifty years, often to celebrate the major role that printing had played in the development of the modern world over the centuries. Many were dedicated to the invention of typographical printing by Gutenberg and the work of the early printers and publishers. Several focused on more technical aspects of printing. The movement was sporadic to begin with, and only began to consolidate in the first half of the 20th century. But what’s really striking in the figures is the very significant increase in the number of printing museums since the 1970s. The main reason for the sudden increase is pretty obvious: for it was during the 1970s that hot-metal composition and letterpress printing were ousted by photocomposition and offset litho as the principal industrial processes.

The social and economic disruption that ensued within the printing trade attracted considerable media attention at the time. It also attracted the attention of academics, promotors of new technologies, and pundits of all stripes who began to talk about ‘the end of print’. All of a sudden printing was news!

On the industrial front, the hardware of letterpress printing suddenly became a glut on a market that no longer existed. The machines and process of an entire industry were being scrapped. And what wasn’t being sold off second-hand to Eastern Europe and the Third World could be had for the asking. Likewise, a significant part of the workforce was also being put out to pasture. A workforce with a strong sense of the contribution that print had made to social, economic and cultural progress over the centuries. A workforce that was proud of its traditional craft skills and know-how. Almost overnight, the dominant industrial printing process had become graphic heritage.

Part of this heritage found its way into existing institutions, such as local history and industrial museums. Some of it found a new home in artists’ workshops. And given the attachment of printers to their trade, some of it became the object of individual initiatives that in the short term saved it from the scrap heap, and in the longer-term lead to the creation of a new generation of printing museums.

As of the 1970s, the modest stream of new printing museums that had begun at the turn of the 20th century became a river in full spate: with over 200 new museums being created over the period we’re looking at. Within these 200 museums the only other sector that showed an increase in numbers comparable to that of printing museums is papermaking, with 30-odd new museums. Though it’s probable that there would have been more book museums than shown here, had libraries – particularly in heritage libraries – not short-circuited them by become increasingly active in organising temporary exhibitions of books during the same period.

The other thing you’ll notice is that the range of museums in the field of graphic heritage became more diverse in the second half of the twentieth century. Printing, papermaking and book museums were joined by a growing number of museums of graphic design, newspapers and printmaking, and more recently, by museums dedicated to printed ephemera, and specialist printed products, including textile printing.

I’d now like to take a look at the context in which all these print-related museums came into being in the space of fifty years.

Fifty years is a long time and, inevitably, things change. First and foremost, the source and the raison d’être of graphic heritage – which is to say the printing industries – have themselves changed beyond recognition. Far-reaching technical, economic and organisational changes have radically altered the structure and status of the graphic industries. I’ve already mentioned the demise of hot metal and letterpress printing. Other major technological changes of the period include the merging of printing and data processing, the irruption of desktop publishing, and the generalisation of digital technologies and media.

The organisation and status of the printing industry were also transformed. Graphic design, and graphic designers, emerged as major players within the printing industry. Desktop publishing ended printers’ five-century old monopoly on graphic production and, more generally, the impact of digital technologies rendered the content of documents largely independent of their supports, profoundly altering the very notion of graphic production, while at the same integrating printing into a seamless continuum of media, of which print is now but one aspect.

For those working in the trade, the transformation of the printing industries was spectacular and, on occasion, brutal. A factor that doubtless played a significant role in the remarkable increase in the number of printing museums. Changing attitudes toward print media also played a part, for the transformation of the graphic industries has never been far from the public eye over the last fifty years.

In the light of all that, it seems slightly odd that so few printing or print-related museums have so far addressed the many questions raised by the transformation of the graphic industries over the last half century, and that even fewer museums have adapted their narratives to take account of the extraordinary diversity of modes of production, distribution and consumption that now characterise graphic production. Why should this be? Why is the period since the demise of letterpress under-represented in printing museums?

One reason of course is that not all printing museums are concerned with recent history or with present-day issues. Many are firmly anchored in specific geographical locations or traditions, or are dedicated to a specialist collection, technique or historical period.

Another possible reason is that the second half of the twentieth century is often seen as being a bewildering succession of generations of machines and processes, most of which are reputed to be difficult to make intelligible for the general public. While it’s certainly true that electronic technologies are less interesting to look at, and more opaque technologically, than the machines and tools of the hand press period or the splendid mechanical presses of the 19th and early 20th centuries, it’s probably less true than is commonly asserted that late-20th century technologies are any more numerous or any more difficult to explain than those of the 19th century. It’s just that we‘ve learned to live with the teeming complexities of 19th century printing processes, by concentrating on only a handful of the most successful, and the most easily exhibited, technologies in order to simplify the narrative. A task of synthesis and selection that has not yet been undertaken for printing in the 20th century.

On a more mundane level, the principal obstacle facing museums who wish to take on the questions raised by the transformation of the printing industries since the 1970s is, no doubt, lack of resources. For such projects are necessarily ambitious and require considerable reflexion and scientific expertise, serious acquisition policies, and the redesign of exhibition spaces and displays. In other words they require personnel, space and serious budgets – all of which are generally lacking in printing museums.

But perhaps the most important reason for the relative absence of the last half century in printing museums is that large parts of the history of printing in the twentieth century have not yet been written!

Now that might seem an odd thing to say, given the number of publications that have been devoted to discussions of the future of print since Marshall McLuhan first made the subject popular in 1962. But the plain fact is that large parts of twentieth-century printing have remained firmly under the radar of historians. Histories of major industrial processes, such as offset lithography, gravure and silkscreen, for example, are as rare as hens’ teeth. As are historical studies of photomechanical processes and photoengraving. And, needless to say, finishing processes – always the poor relation of the printing trade – remains resolutely beyond the pale. Even the technologically sexier aspects of modern printing, such as electronic pre-press, await their historians.

It would appear that the economic and industrial histories of the momentous half-century of innovation and restructuring that the graphic industries have traversed have stalled somewhere along the way. Not that that has in any way diminished the appetite for discussions and speculations about the future of print culture among specialists who seem to be quite unperturbed by the absence of a reliable historiography of the technologies and modes of production that, logically, ought to inform their chosen subject. Again, we have to ask ourselves, why such indifference? Why has twentieth-century printing remained such a blind spot for historians of print culture?

Fifty years ago, printing history was a thriving cottage industry. As a discipline it was on the margins of academia, but it seemed to be actively developing an identity of its own, emerging from the shadow of bibliography which, for well over a century, had been one of the driving forces of the history of the book and typography. Emerging also from the no doubt venerable but never quite respectable tradition of the printer-historian whose intimate knowledge of the trade, its techniques and its practices, was sometimes betrayed by a certain unfamiliarity with the methodologies of professional historians. Printing history was also giving birth to learned societies on three continents, and a growing number of scholarly journals and monographs was being published.

The intellectual climate also seemed favourable. Historians were becoming increasingly interested in local traditions, oral culture and everyday life. And the rise of cultural history and material culture was also creating an environment that was, in theory at least, conducive to the development of printing history. Printing history was particularly fertile ground for cultural history because it covered both the highbrow and the popular. And, indeed, both printing history and printing museums were able to capitalise on policy makers’ increasing interest in material and immaterial culture to promote the preservation and transmission of the traditional, often unwritten, craft skills of printing.

The growing success of cultural history was, however, double-edged for printing history, because it opened the door to newer disciplines such as media history and book history which, though often rooted in traditional fields of study such as newspaper history and bibliography, were generally seen as being more in tune with the times and with academic research criteria. Book history in particular was proving more attractive than printing history for humanities students with an eye on the positions that were opening up in the new field of print culture. Book history was also double-edged because its practitioners tended to consider that questions of print production had already been largely dealt with by printing historians. As a result, book history largely abandoned the study of the means of print production, with the exception of material bibliography which generally focused – and continues to focus – on the hand press period. The cutting edge of book history research moved on to deal with the book trade and modes of diffusion and, more recently, questions of reception.

What can we conclude from this brief look back over fifty years of printing museums?

Perhaps the only conclusion we can draw with any certainty is that the death of an industry can be good news for museums! For the demise of letterpress printing proved to be a windfall for printing museums. It provided the tools, machines and furniture (in every sense of the term) for an extraordinary number of new printing museums and heritage workshops around the world. It also provided the know-how to keep the material heritage alive with the hope of transmitting it, at least in part, to future generations.

It was a one-off event, however, for the printing industry wasn’t just any old industry. Letterpress printing had a particularly noble ancestry going back five hundred years, all the way to Gutenberg. It was a noble technology that had transformed the world. But it was a technology that had served its time, and towards the end it had even been living on borrowed time, stalked by the photomechanical, electronic and computer technologies that finally swept it unceremoniously aside. And as the technology was swept aside so were the skilled and unskilled workers, the know-how and the experience.

But, today, printing museums find themselves on the cusp of change.They have relied heavily on the human, intangible heritage of printers for at least two generations. Unfortunately, our reliance on the generations that had exercised their skills as practising printers can’t last forever. Also technological change in the printing industry has now become so commonplace that, as succeeding generations come and go with the seasons, they leave almost no trace – or at least no trace comparable to that left by letterpress printing.

At the same time, the unprecedented wave of new printing museums has been accompanied by a significant hiatus in the pursuit of printing history, which has found itself marginalised by the rise of younger disciplines. I’ve mentioned book history, and had there been more time there would have been a lot to say about graphic design history and media history among others.

So the question ‘Why do people make printing museums’ is nothing if not pertinent. It’s quite possible that the great wave of new printing museums that we’ve seen since the 1970s will decline in coming years. But the diversification of museums committed to graphic heritage will certainly continue. People won’t make printing museums for the same reasons as before. Perhaps they will hardly make printing museums at all, at least as we know them today, as hybrid, cross-media become the norm of the digital age, and as the once easily-identified printing industry, proud of its technology and craft, becomes a distant memory.

My focus today on the need to take account of the transformation of the printing industries in the second half of the 20th century has doubtless been informed by my own personal experience in the course of a long collaboration with the Museum of Printing and Graphic Communication in Lyon. But I’m convinced that similar issues exist in many other areas of graphic heritage and that each of us in our own way is affected by the profound changes that have taken place in the printing industry.

However, for most of us that doesn’t mean changing our collections, missions, narratives, exhibitions. Rather, it’s a question of how we situate our approach to such questions with respect to the changes that have affected print culture in the last half century, and with respect to changing perceptions of print culture in society at large. The last half century has undoubtedly been exciting for all who have been involved in the printing museum adventure. But as it has progressed, and as the graphic heritage scene has become ever richer and more diverse, it has opened up a whole new series of issues for printing museums. Some of these issues present themselves today as the ‘blind spots’ of the title of my talk. But whatever we choose to call them, without exception they open up new perspectives for the development, visibility and better understanding of graphic heritage.