Talk in two parts given by Katharina Walter and Ulrike Koloska (Berlin, Germany) at the conference of the Association of European Printing Museums, Safeguarding intangible heritage: passing on printing techniques to future generations, held at the Nationaal Museum van de Speelkaart, Turnhout, Belgium, 23-26 May 2019.

Future aspects for research, handcraft and museological practices

Katharina Walter, Image Knowledge Gestaltung, Humboldt-University, Berlin, Germany

We thank the managing board of the AEPM for the invitation to speak here at this conference about the very serious problem of how to safeguard printing heritage. Ulrike and I have both been confronted with the impending or even ongoing loss of the techniques of letterpress printing within different academic contexts such as interdisciplinary projects, conferences, workshops and teaching. On several occasions we attended rather lively debates about preservation measures with curators, printers, designers, book artists, as well as publishers and people of all ages.

With this presentation we seek to explore our role as historians a bit further and wish to examine our task in this heterogeneous network of institutional and individual actors. First I will present some thoughts on how currently the material and practical turn in cultural and media studies might support the call for preserving printing techniques. In the second part, Ulrike will outline how the heritage workshop could provide a field of experimentation for artistic research. Overall, we will present two ideas of the workshop in terms of what is nowadays defined as a laboratory: a place where knowledge is constantly applied, approved, experimented with and generated.

Heterogeneous concepts of ‘preserving letterpress printing heritage’

Let me first introduce you to the very complex network of actors pursuing the overall aim of ‘preserving letterpress printing heritage’. A closer look confirms that they partly do not agree on what they understand the preserved object to be, on what their purpose is or how they interpret the problem.

- Museums and academic institutions seek to preserve, explore and mediate historical printing heritage in all its different forms – as a craft, a technology or printed artefacts – through archives, exhibitions and publications.

- Apart from these institutional players, we have the professional typesetters and printers to whom printing is foremost a complexity of craft skills and traditions to pass on to future generations. In this group we have what I call a new kind of entrepreneur-printer who defines printing less as a static but more as a dynamic concept. For such entrepreneur-printers, preservation does not exclude experimentation with digital technologies.

- Furthermore we have the book and graphic artists maintaining printing mostly as a handcraft, which serves as a tool for artistic experimentation.

- Finally, and importantly, there are the art and design schools that think of preserving or re-establishing workshops in order to teach design students a deeper understanding of the material origin of digital typographic tools.

We realise that all these positions differ extremely in conceptual terms. First, what is actually perceived as intangible heritage – the pure handcraft or mechanical forms? And secondly, what do we mean by ‘preservation’ – ‘conserving’ a current status quo which derives from the 1970s when the last professionals were trained? But understanding ‘heritage’ not only as a retrospective, but more as a future-oriented concept, preserving ‘the old’ is not an end in itself. It aims to provide a stock for experiments and future development. We see that any concerted strategy for safeguarding printing heritage would require first a stronger conceptual agreement among the actors involved about the object and the purpose of preservation.

Printing as tacit knowledge

But what might the interest of a cultural and media historian be in maintaining the know-how of a printer? Of course, a historical researcher is aware that modern printers do not provide direct access to any historical setting. But while the historian’s knowledge about printing relies generally on interpretation of written documents and illustrations, the printer gains insight just by practising. Craftspeople in general incorporate a sort of knowledge about the making of things, which cannot be verbalised or written down, but is routinely performed. Already Joseph Moxon outlined in the preface of his Mechanick Exercises, published in 1683, the specific epistemic aspect of craftwork: ‘Handy-Craft […] cannot be taught by Words, but is only gain’d by Practice and Exercise […].’[1] About three centuries later, the Hungarian philosopher and chemist Michael Polanyi attached a wider intellectual and social dimension to what he called now ‘tacit knowing’. In his work Tacit dimension he claimed in 1966 that ‘we can know more than we can tell’.[2] It is this performative transfer of skills, ideas and experiences that keeps this knowledge alive and effective far beyond written documents and illustrations.

Printing as a media archaeological field

This enormous cultural dimension of implicit knowledge has become a key factor throughout the epistemic shift in the humanities towards material and practical aspects of culture since the mid-1980s, foremost in cultural and media studies. In this new context, techniques, practices, machines and instruments have gained the researcher’s main attention. The symbolic and the technical sphere of culture, that is to say representation and production, were no longer interpreted as distinct but as inherently interactive. This ‘material turn’ also gave birth to a new research field called media archaeology. It follows a completely new idea of how the history of media technology might be explored, written down and archived. I will outline very briefly the main assumptions and reflect on the question to which extent a printer may be defined as a media archaeologist.

Media archaeology, as the term already implies, does not process the past by historical narration, but approximates its objects in an archaeological manner, as German media scholar Wolfgang Ernst explains: ‘Archaeology, as opposed to history, refers to what is actually there: what has remained from the past in the present like archaeological layers, operatively embedded in technologies […]. “Historic” media objects are radically present when they still function, even if their outside world has vanished. Their “inner world” is still operative.’[3]

It seems clear that these media excavators refuse to think of history in terms of a linear process throughout which old technologies have been progressively replaced by new. It is more about transformations which keep the past still effective in the assumed new. ‘This is slightly different than considering past artefacts as dead media’, Finnish media scholar Jussi Parikka claims.[4]

In this perspective the Johannisberger stop-cylinder press from 1924, restored in the 1980s and still working at the Lettertypen in Berlin, this press might be designated as a media archaeological object. For a compositor and printer this machine is not historical in first place. He works upon its historical layers while simultaneously adding a further layer through implementing new technical features such as brushes and doorstops, a perforation wheel or combining it with digital typesetting and photopolymer plates (fig. 1–5). This is why Ernst underlines that media systems create their own ‘Eigenzeit’, their own temporality.[5] They do not display a single step in a timeline, but an archaeological ‘deep time’.[6]

It is this interest in media remains, which is also particular to the media archaeologist’s research. According to Parikka, remains could confront us with the ‘multiple other times that still persist: the time of the old, the obsolete, the fading, the slowly emerging, the parallel, the returning, the deep time, the time that is not reducible to a linear history. So many times.’ [7]

In this concern a printer might be seen as a kind of practical researcher digging into one of the deepest media systems, which is printing, just by operating on the basis of implicit knowledge.

It needs this collaboration between practical know-how, historical research and museum archives to find out more about this still enormous archaeological field, especially when we think of all the other remains of the 20th century such as the phototypesetters, offset-printing machines, and so on. In this sense, we have to imagine a new concept of a printing workshop, which is defined as a physical space where the ‘knowing that’ and the ‘knowing how’ things work, constantly interfere with each other. Without a doubt, historical research must integrate academic, museological and technical work to a new great extent.

Now Ulrike will shed light on the artistic and art historical dimension of the printer’s workshop.

Script – Image – Knowledge

Experimental printmaking as concept of ‘Performative Science’ [8] in the example of the Werkstatt Rixdorfer Drucke

Ulrike Koloska, Seminar on Artistic-Aesthetic Practice, Humboldt-University, Berlin, Germany

Jean Marie Leroux, L’art s’illustre par la science, la science se perpetue parl’art, copper engraving based on a drawing by Jean Galbart Salvage, 1812.

The aim of this part of the lecture is to outline to what extent we can understand the printing workshop as a laboratory of knowledge. My goal is to do so by revealing the interdependence between artistic practices and technological spheres in relationship to historical printing techniques. I will examine three strategies in the example of the Werkstatt Rixdorfer Drucke, which was a place where historical book-printing entered into substantial relation with experimental-artistic work and technical-crafted production.

Strategy I: Disarrangement/Deconstruction as a creative strategy for a new perception and perforation of printing tools and techniques. Questioning existent implicit knowledge

Founded in 1963 in Berlin Kreuzberg – in the context of a manifold cultural environment and the emergence of a milieu with subcultural autonomy – the artists of the Werkstatt Rixdorfer Drucke developed into an artist group that combines traditional printing techniques and materials with experimental artistic procedures. Their series of graphic works, portfolios and artist’s books are evidence of the concentration on the processes of their genesis – these are processes in the material and technical as well as in the intellectually constitutive sense.

The printing workshop was filled with strange objects and various historical craft tools and machines. Similar to the ‘cabinet of curiosities’ principle – aiming to make the objects and instruments of research into show-pieces for our admiration – the workshop‘s facilities, as well the refinement of their arrangement is aesthetically appealing rather than just functional. This means that the processual emergence itself becomes visible in form of production and materiality.

With a printing bed capable of printing 70 x 100 paper size the Kempewerk-proofing press is situated in the center of the workshop, so that the participants can circle around it.

Wood- and lead types are stored in letter-cases, labeled with the lettertypes which they contain – not with their technical terms.

Letter cases in the workshop Rixdorfer Drucke in Gümse, Wendland, 2017.

Additionally, there are diverse typefaces and printing forms acquired from book printing workshops which were closed in the beginning of the 1960s. The workshop‘s facilities – in seeming disorder – do not follow a mechanical system in the sense of a professional typesetting workshop. Instead they are organized in a kind of creative arrangement.

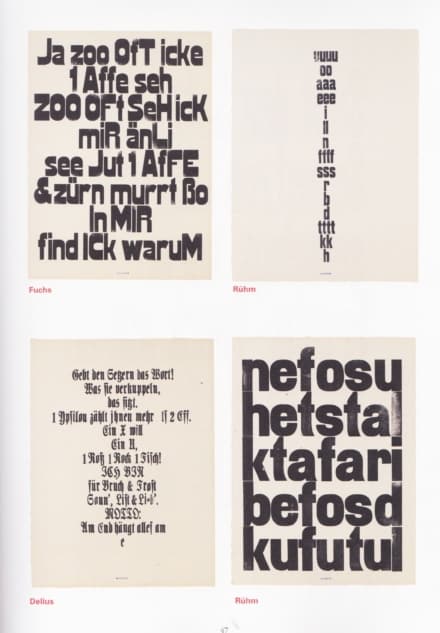

With a limited quantity of wood and lead types the Rixdorfer artists and their befriended poets manufactured typographic artefacts with the greatest possible utilisation of the letter-material by typesetting directly on the press.

Confronted with the restricted options of letters to choose from, all workshop participants found themselves in a constant dialogue between the formal rules of typography – or rather their deconstruction – and their poetic intention.

The motto ‘Am End hängt alles am e’ (In the end everything depende on the ‘e’) expresses pointedly and ironically the synthesis of poetized word and script image of the word, bringing together word and image as one in the characteristic creating process in the Werkstatt Rixdorfer Drucke. Thereby the material‘s limitation plays a major role. If there is an ‘e’ missing in the type case, this gap becomes the artistic and literary muse, the driving force of new creations of forms and words.

The workshop’s atmosphere, the diverse arrangement of machines and materials as well as the rhythm, sound and the distribution of roles in the printing process respectively, the ‘disarrangement of the normal’ [9] establishes a workshop character that offers a space for performative approaches to image processes and for gaining access to material culture in an artistic, experimental way.

The choice of letters for a new text by the artists in this disarrangement appears very systematic and organised. In each round of printing, the complex distribution of roles follows a consistent rhythm. From inking the printing block by Ali Schindehütte to the placing of the papersheet through Josi Vennekamp to turning the press-crank by Uwe Bremer, the separate workstages generate a continuum, that frames the open process of creation and eventually resonates in the consistent print of the text-image-sound-structure.

“(…) Because there is a big difference between talking about a thing or doing the same thing. (…) Because the mind has to start using it to grow, so that the hand can do what the mind wants. From this, over time, the certainty of art and use grows. Because these two must be together, because one without the other is nothing.” [10]

The notion of use, which Dürer understands in the sense of a manual skill, a knowledge of the hand and which he relates to the artistic creative process, this notion of ‘use’ encourages us to deal with the relationship between hand and mental processes with regard to the development of a system of visual strategies. This concept of use as developed by Dürer allows us to understand the transformation of technological processes into a syntactically dense and complex image system.

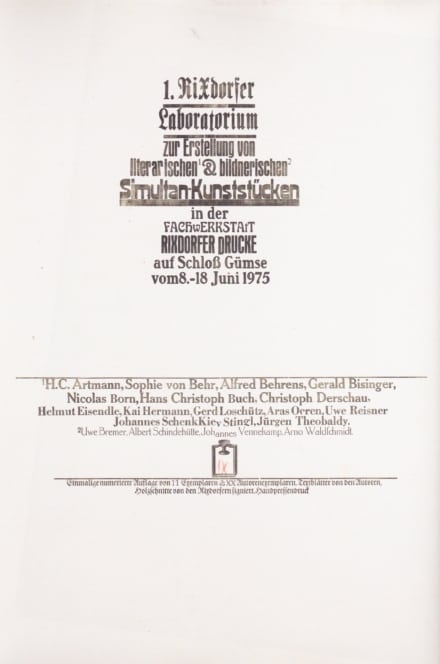

Strategy II: Simultaneity of writing, typesetting and imaging

After the relocation from Berlin to a cottage in the Wendland in 1974, the Rixdorfer printing workshop became a center of significant encounters for artists, writers and various cultural and political actors. The so-called 1. Laboratorium zur Erstellung von literarischen und bildnerischen Simultan-Kunststücken (1. laboratory for creating literary and visual simultaneous artefacts) in 1975 refers to the character of the laboratory in the work process on the one hand and reveals the simultaneity of actions as central theme in the creative process on the other hand.

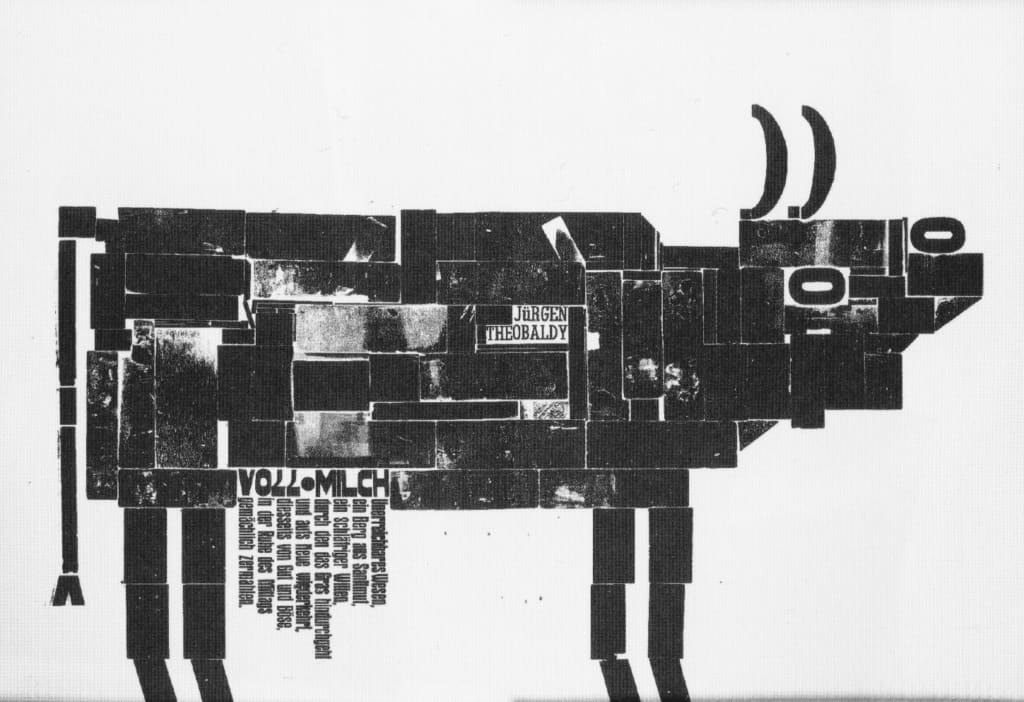

In addition to the programmatic title of the graphic collection Simultanmappe from 1967, the typographics point to the core of the creative process of the Werkstatt Rixdorfer Drucke: to the simultaneity and reversibility of the translation procedures from text to typeface to image in the printing process. Creating poetry, setting and printing take place simultaneously, they condition and influence one another. The result is a homogeneous picture-text structure, where a shift of the pictorial into the written and from the written into the pictorial takes place.

By reversing, shifting, and displacing letters, they are no longer legible in their semantic meaning, but instead turn into signs and become ciphers, figures, and forms that are perceived in a new context.

Fine irony, satirical connotations of words, sayings and language thus become depictable and appear to the viewer as dismantling, as literal breaks in the truest sense. All the associative power of the word is explored in the game with letters and the new combination of word-and-sentence-contexts. In the printing process it is transformed into script-image or wordimage. In his weird depiction, the word is constructed and deconstructed at the same time, simultaneously charged with meaning and counteracted. It has the necessary blurredness, that is needed and exploited in the experiment, in order to widen the horizon of options.

Strategy III: Accesses to historical objects, materials and the knowledge of craft techniques by practice-based museum strategies

Experimental approaches that are incorporated into museum strategies allow for renewed access to historical objects, materials and the knowledge of craft techniques. This is achieved by getting engaged in the process. Apart from an authentic experience of craftsmanship, the focus is on the practice-based research methods on and with artifacts like machinery, tools, paper, printed works etc. for the purpose of an experimental image- and media archeology.

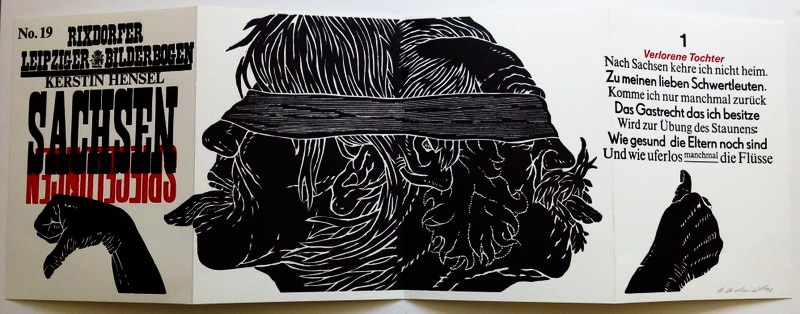

As part of a cooperation project with the Museum für Druckkunst Leipzig, the artists of the workshop Rixdorfer Drucke in 2006 developed the Rixdorfer Leipziger Bilderbogen no. 19′ with texts by Kerstin Hensel.

SachsenSpiegelungen, Kerstin Hensel, Rixdorfer Leipziger Bilderbogen, 34,5 x 98 cm, Museum für Druckkunst Leipzig 2006.

In a kind of interactive exhibition, the portfolio ‘Sachsenspiegel’ was produced on site and then presented in the Leiziger Haus of the book. In the process, the graphic sheets, which were later folded as Leporelli, were printed by the artists of the Rixdorfer Werkstatt in the Leipzig Museum of Printing using the historic printing presses and tools.

Focusing on the transformation processes from text to script-image in the mechanical process of the letterpress printing, the exhibition of the Rixdorfer Drucke workshop was able to investigate to what extent developments in media and technological history have a significant influence on the artist’s creative work. This brought into focus the creative potential inherent in the printing process in order to sharpen our awareness for historical continuities as well as for profound transformations in the relationship between traditional scientific research and artistic practices. In the sense of a museum as laboratory, it could open up perspectives on a completely new material culture.

Photo credits

Photos 1-5: Max Zerrahn and Die Lettertypen.

Notes

[1] Moxon, Joseph: Mechanick Exercises, or the Doctrine of Handy-Works. Began Jan. 1. 1677. And Intended to be Continued. London 1683, Preface (unpaginated).

[2] Polanyi, Michael: The Tacit Dimension. Chicago 2009, p. 4.

[3] Here Wolfgang Ernst refers explicitly to Martin Heidegger, Sein und Zeit (Tübingen 1986), p. 380. See Ernst, Wolfgang: »Media Archaeography: Method and Machine versus History and Narrative of Media«. In: Erkki Huhtamo/Jussi Parikka (eds.): Media Archaeology. Approaches, Applications, and Implications. Berkely 2011, p. 241.

[4] Parikka, Jussi: »Remain(s) Scattered«. In: Ioana B. Jucan/Jussi Parikka/Rebecca Schneider (eds.): Remain. Minneapolis 2018, p. 15.

[5] Ernst 2011, p. 241.

[6] Zielinski, Siegfried: Deep time of the media. Toward an archaeology of hearing and seeing by technical means. Cambridge 2008.

[7] Parikka 2018, p. 10.

[8] Hans H. Diebner (eds.) Performative Science and Beyond, ZKM, Springer, Wien/NewYork, 2006.

[9] Heidegger, M. Beiträge zur Philosophie Vom Ereignis, Gesamtausgabe 65, Frankfurt a. M 1989.

[10] Albrecht Dürer in the aesthetic discourse at the end of the 3rd book of the theory of proportion, Nuremberg 1528.