Richard Ardagh, The Type Archive, London (UK)

Talk given by Richard Ardagh, The Type Archive, London, United Kingdom, at the conference of the Association of European Printing Museums, Safeguarding intangible heritage: passing on printing techniques to future generations, held at the Nationaal Museum van de Speelkaart, Turnhout, Belgium, 23-26 May 2019.

I’d like to warmly thank AEPM for letting me speak and begin with an apology: I’m not an academic, so my talk today will be given through the lens of my own experience, rather than being based on scholarly research.

Within the framing of this conference, I am a fortunate recipient of the intangible printing heritage you are looking to safeguard, and am very grateful for it. I’m certainly someone who learns best through doing, and I’ve relished the opportunity to be hands-on through my apprenticeship at the Type Archive, which has managed to preserve the skills I’m going to talk about, and keep them alive, through practice, for a quarter of a century now.

So, to introduce myself: I am a graphic designer with my own practice, designing books mainly. My interest in typography and print led me to letterpress and, having got a taste for it, I’ve been falling further and further down the rabbit hole ever since. I’m also a partner of New North Press, a letterpress studio in London, and it was on behalf of New North Press that, in 2014, I commissioned a prototype 3D-printed letterpress font, called A23D. The project was a very interesting exercise – with intricacies I won’t go into today – but despite understanding a fair amount about letterpress at that time, it really made me realise how limited my understanding of the traditional techniques of producing type was. I had seen Monotype and Linotype casters working but the journey that a letterform took in its transformation from a drawn sketch to a physical piece of type was a bit of a mystery, or at least one that I could only describe by reciting what I’d read in books. So when the opportunity to observe, and later practise the stages of punchcutting and production of matrices arose, it was one I jumped at.

The Type Archive concerns itself with the engineering of the word, and holds typographic artefacts dating back many centuries, but one of its original reasons for being was the preservation of the Monotype system of hot metal typecasting. This system had brought about the mechanisation of both the production of type and its setting, and the Monotype Corporation served the whole world with the equipment to make this possible: keyboards, Composition and Supercasters, matrices and diecases; all of which it manufactured and distributed.

Following the comapny’s demise, in 1996, 900 tons of machinery and equipment were moved from Monotype’s base at Salfords in Surrey to the ex-animal hospital in Stockwell, South London that would become the Type Archive. (The delivery of the 23,000 drawers of punches and matrices took two ten-ton lorries, making daily visits, seven weeks. And the plant and machinery took a further week with two sixteen-ton lorries. The move was nicknamed Operation Hannibal.)

The Monotype Corporation had been a huge operation. Actually, the equipment that came to Stockwell was just enough of the plant to keep production running. That meant, in the most part, one of each machine, plus the archive of punches, matrices, charts and records.

Thinking back, my early impression on visiting the archive was one of awe, both at the extent of detail involved in the various processes, but also at the scale that things must once have operated at. There was also a mental adjustment that came gradually as I understood that, although I was approaching from a design perspective, what I was encountering was in fact precision engineering. Where I saw Baskerville, the other staff saw a number: 169 (the Monotype series number).

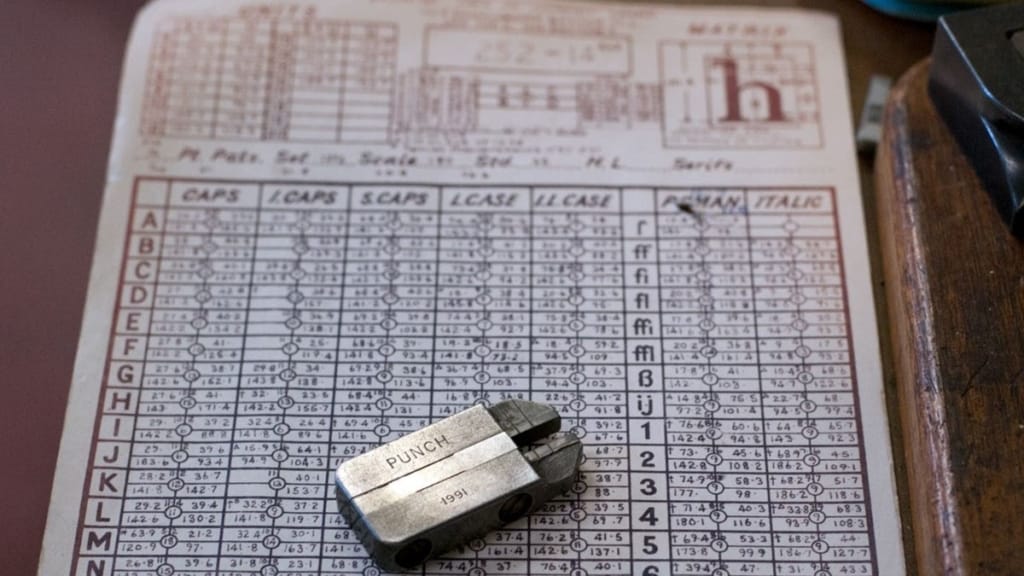

This slide shows the chart for 252 (or Centaur to you and me). It shows measurements for the scale and placement of every character in the font in units of ten-thousandths of an inch. This is 14pt, there are separate charts for every size that a font is cut in. And they’re all handwritten.

In the punchcutting department at Monotype there were 10 machines operated daily and this was just one department in a huge production line employing thousands. In the factory, typically each task was separated: if you drilled cone holes you would not operate the side milling machine. So it is extremely fortunate that my tutor, Kumar, was friendly enough with his foreman to go against this convention and managed to learn to use all of the machines involved in the production of matrices.

Parminder Kumar Rajput is who I have been studying under, and the fact that I’m able to stand here and talk today is really a tribute to his patience and encouragement. With nearly 60 years experience, he is certainly the master and I am certainly the novice. At Monotype, the training period to learn punchcutting was 3 to 5 months, full-time: five days a week. My apprentiship has been one day a week for a year and a half while juggling other projects, so there is still quite a way to go to before I can call myself confidently proficient.

So, now that I have given you context I will come on to the specifics of the punchcutting process. I have tried to distil what I’ve learned to describe to you today but, it’s worth noting that in reality, the production of punches and matrices isn’t as straightforward as following instructions. The understanding of the purpose of each process, as well as how to operate the machines – which can be temperamental – is a necessary ingredient. Having a person like Kumar to guide me, remind me, and remind me again, until the techniques and reasons fall into place, has been crucial.

What is punch cutting? Punches are master letters, and the first significant stage in translating a drawing into metal type. They are typically cut in steel and driven into a die, or matrix, from which multiples can be cast easily. For centuries punchcutting was done by hand with a graver; a method of manufacture reliant upon highly skilled craftsmen. But – to paraphrase Monotype literature – when a punch broke during the striking of a matrix, no amount of human skill could ensure that any second punch could be made so precisely as to be microscopically indistinguishable from the first: such a feat is possible only by machine.

The vertical pantograph machine at the Type Archive was designed by Frank Hinman Pierpont and manufactured by the Monotype Lanston Corporation from 1907 onwards. It’s very similar in principle to Linn Boyd Benton’s designs of the 1880s. The operator uses the stylus on the lower end to follow the outline of the enlarged pattern of the character. The upper end carries the steel punch which is worked around a cutting tool revolving at very high speed (10,000 revolutions per minute).

There are, however, stages necessary before you can begin cutting a punch. Each character of the typeface design is rendered as a 10 x 10 inch outline drawing, from which the proportions and boundaries can be established within the Monotype 18-unit system. This is scaled down to a quarter size pattern on which the character is raised from the surface. Traditionally this was done using wax and forming a copper plate. The means to use this technique have unfortunately not survived but we have been able to fabricate equivalent patterns using CNC routing.

With such a large existing archive of punches and matrices at the Type Archive, the need to cut new punches is not great. However, I have been fortunate that my apprentiship has coincided with an exceptional commission: the production of Hungry Dutch, a typeface designed by Russel Maret and the first new Monotype series for composition casting in over 40 years. This commission has provided a practical reason to understand, practise and document the punch cutting process, and is a case study of great benifit. As of this week, we have just recieved patterns for the last 10 glyphs so we can cut the punches that will complete the roman character set.

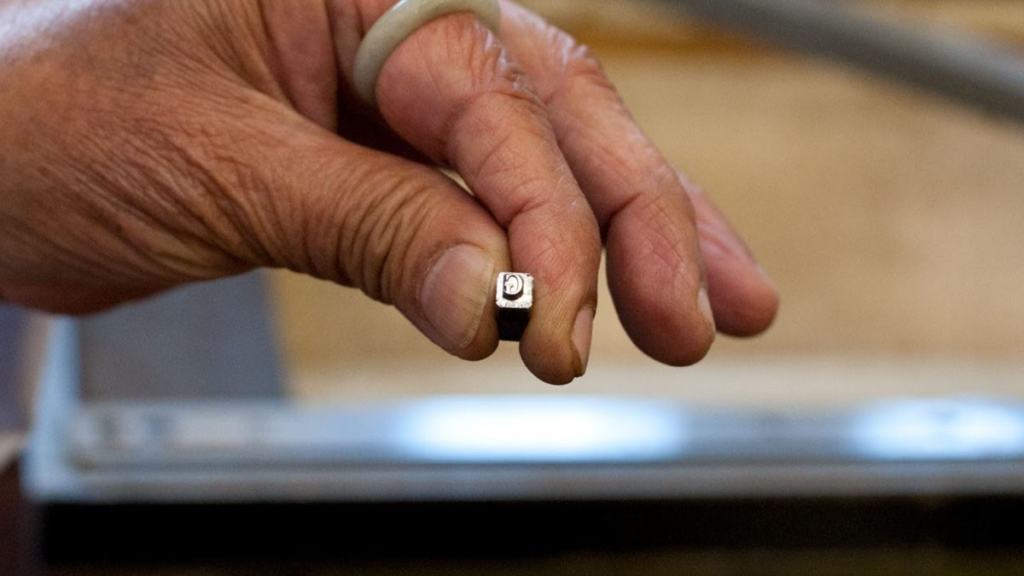

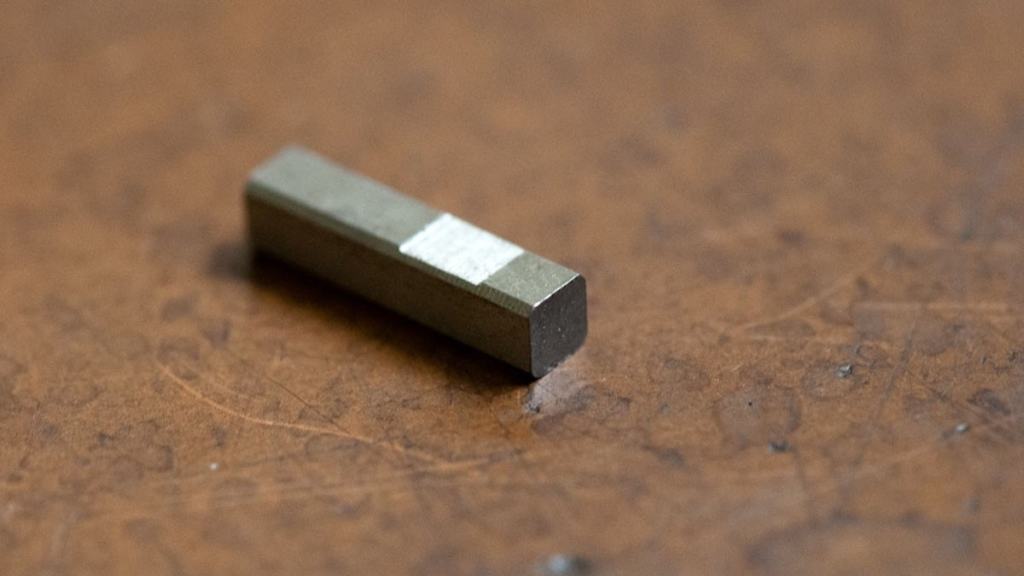

Here is a 0.2 inch (5mm approx) blank steel punch. The metal is reletively soft when it’s cut, the hardening comes later. The punch’s surfaces – particularly the face – are rubbed smooth on various grades of Indian stone before cutting to ensure the surface is completely flat and unblemished. Grease is also repeatedly applied throughout the cutting process.

Having loaded the punch into the top of the machine and with the pattern fixed at the bottom, the cutting can begin by tracing around the character with the stylus and a series of followers, which are housed in the cartridge above for easy access.

The followers are disks of various size, fixed to the end of the stylus in a sequence of decreasing diameter, while cutter depths are also adjusted to work up to the face. The cutter tool cuts shallower as its brought nearer the face of the letter with each circuit. There is a whole cabinet of followers, the selection of which depends on the scale of the finished type required.

Here we see the cutter tools and, on the right, enlarged models used for teaching. The first is a milling tool, used to remove the larger unwanted areas around the character; the second is a chisel cutter which begins to define the outline; and lastly, the final cuts are made with the point tool. The process is a gradual one, typically using 2 chisel cutters before finishing with the point cutter. In some of the final cuts only 0.00004″ (0.001mm) of metal is removed.

It’s worth noting that these cutters themselves have to be painstakingly sharpened in similar multiple stages. Cutters are checked on a machine called a Shadowgraph which magnifies the tool 200 times in order to ensure 10,000ths-of-an-inch accuracy before cutting.

This is an animation which compiles the roughly 30 stages as running in sequence.

The sides of the punch must be bevelled so the it can be removed without damage when striking the matrix. For strength, the character’s counters are raised and ‘saver’ wedges protect thin walls around the outside.

Once all measurements have been checked against the chart and any burrs have been removed the punch can be tempered in preparation for striking. The punches are placed in an oven in pairs for 6 minutes at 850 degrees, then plunged into a bucket of oil. The punches are then tested for strength using an industrial pressure gauge. Measurements are checked again and punches are ‘justified’.

Then a matrix can be struck. The stamping machine applies 20 tonnes of pressure. If there has been any distrotion in the striking, the babble is ground to compensate so that the position on the matrix is accurate. (If the babble is too large on one side the stamping can push the character position off target.) The distortion of the outer dimensions of the matrix are corrected later.

I have felt very proud to see the finished type marching off the composition caster. But, according to Monotype literature, the final satisfaction is still to be realised: ‘It’s only in the printing of the finished type, when the inked impressions of the characters appear on paper and form recognisable word shapes under the reader’s eye that the punch cutter sees the end product of his skill.’

I should make it clear that the Hungry Dutch project is not the product of my labour alone. I need to namecheck Nick Gill for breathing initial life into it; Graham Sheppard who produced the drawings; Kumar for applying his knowledge and skill and sharing it with me; Duncan Avery for managing the project; and, of course, Russell Maret for his design and patience. Also Sue Shaw for her consistent dedication to the Type Archive.

The Type Archive is a truely unique place, housing, not only pre-eminent collections of the history of typographic manufacture, but carrying forward their intricate understanding and practical skill sets through its dedicated staff. It is now poised to offer fantastic opportunities to those seeking to further their knowledge in typographic engineering and invites all interested to make themselves known. As recognised by all in this room, there is an ongoing need to preserve these skills and pass on the invaluable knowledge we have helped preserve.

I would like to close with this thought: The preservation of traditional skills through practice is important, but perhaps as important is imagining new ways of them being used.