Talk given by Dr Dorothee Ader, director of the Klingspor Museum, Offenbach, Germany, at the conference of the Association of European Printing Museums, Why do people make printing museums, held at the Atelier-Musée de l’imprimerie, Malesherbes, France, 5-7 May 2022.

Dear colleagues, dear AEPM members, thank you very much for the introduction and the invitation to talk today about questions that we have probably asked ourselves several times before. One of our questions today is, how can we adjust our museums to the future? How can we remain relevant with our topics in the future?

This is the AEPM conference, so we all deal with printing somehow, usually from a historical point of view. The Klingspor Museum primarily collects the products of printing, especially printed artworks, for example by Wilhelm Neufeld, Hendrik Nicolaas Werkman or Frans Masereel. We also collect modern and contemporary book and type art, this means artists books, illustrated books, childrens books, tapestries, calligraphy, type design, communication design, posters and so on, beginning in the year 1900. We take care of about 80,000 items, a very important collection which includes the type designs of the typefoundry Gebr. Klingspor, which previous to 1906 was known as Rudhard’sche Gießerei (Rudhard Typefoundry). The typefoundry suffered huge damage in World War 2, so a great amount of archive materials have been destroyed, but we still have a decent collection of type specimens and process material we can work with. And we also have a printing workshop with machines for letterpress printing, lithography and engraving that is used by artists as well as for our educational programs (Picture 1). It’s a place I’m personally very fond of, and it is with no doubt a beautiful place, but with an anachronistic air, I have to admit.

We all collect knowledge on old printing techniques, we collect machines and other materials for printing and in the case of the Klingspor Museum also art. And we all fight against the loss of knowledge by trying to preserve the objects and the technology and this is of great importance, because printing is a cultural technique that has formed our societies. But I want to ask nevertheless: Is this enough? Is it enough to simply preserve, just because we are afraid of losing knowledge? Knowledge that will never be in real use again if we are honest with ourselves. So why are we doing it anyway? What is our contribution to society?

If we take a close look at the tasks of a museum, we come up with the following list: a museum should collect, preserve, research, exhibit and educate or mediate. All these important tasks, that are, of course, necessary to gain some professionalism, have a problem in common: one way communication, from the museum to other people, and thus creating the perfect bubble. We decide what to collect, what to preserve, what to exhibit and what to mediate. And of course we are in constant exchange with colleagues and with scientists and with visitors who choose to come to our museums, and I really don’t want to talk this down, but I think, to remain relevant with our topics in the future we need to add another task and this is listening, opening up to ideas of a wider society – two-way communication. I‘ve worked in museum education for many years, especially with people, who didn’t chose to come to the museum, who weren’t especially interested at first, because they had to come with their schools or other institutions. People who just started learning German or who are not alphabetised at all, or suffer from Alzheimer’s disease, or are madly in love, or whatever. So my point of view is of course influenced by these experiences and I‘ve learned over the years that there is one huge resource we don’t choose to use in our daily museum work: and this is ideas and knowledge of a wider society. And by that I don’t mean an academic knowledge or a knowledge of technical support, I mean people’s view of their living conditions for example, I mean children’s and young adult’s attitudes and opinions on our living together, their view of questions and problems, of politics as well. And the best thing is, once properly asked, most people are more than willing to express themselves and to share their thoughts.

And at this point I’m very glad that we are all working in printing museums because this provides us with a great opportunity to use these resources and to actually listen. Printing is always expression. Printing means of course certain techniques but in the first place printing is a method – a method to form, focus, formulate and distribute thoughts. And this is something our museums can easily offer!

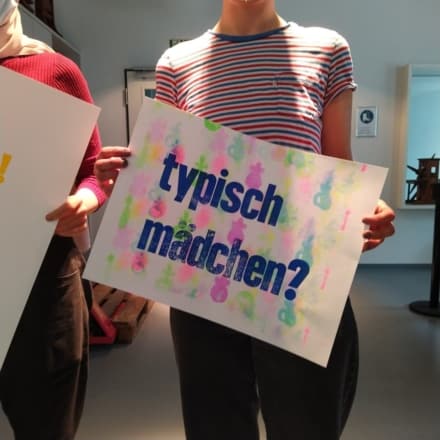

In the educational work at the Klingspor Museum, the subject of printing plays a role in the examination of artistic printed products and also in printing itself. In order to make these treasures approachable for young people, the museum works closely with schools, day-care centres, the youth education centre and the women’s office of the city of Offenbach. In these cooperative contexts, numerous projects have been implemented with young people, in which the themes of self-determination, self-expression and, in general, empowerment through printing were and are central. (Picture 2) The question shown here means ‘typically girl(ish)?’ in English, because young women still deal with a lot of implemented expectations on their female role in families, in school or at work and these young women wanted to point that out.

An ongoing series with young people at the Klingspor Museum, for example, deals with the questions ‘What is important to you?’ and ‘What do you draw strength from?‘ The lithographic painter‘s book La clau del foc by Antoni Tàpies from 1973 is the starting point for each of the reflections. Born in Catalonia, Tàpies (1923-2012) grew up under Franco’s dictatorship after the Spanish Civil War and developed a strong awareness of the suppressed Catalan identity, language and culture. Tàpies’ extensive oeuvre of paintings, material pictures, sculptures and prints reveals an irrepressible delight in relief-like surfaces and haptically interesting materials. Even his prints are often lifted out of the surface by means of collages, embossed prints and strong colour application and are characterised by a great love of experimentation. In his desire for personal expression, Tàpies disregarded all the conventions of printing techniques. In the 1950s, he made lithographs with sawdust or with ink squeezed through cracks in the glass; later he developed embossing techniques that could be combined with lithography, pressing his hands onto the printing plate or running over it. Books also play a major role in Tàpies’s graphic work, and a total of over 50 titles were produced together with various publishers, authors and printers. For La clau del foc Tàpies designed a pictorial programme that evokes in many motifs the fighting strength of the Catalans for their endangered identity in the 1950s. In one particularly strong double-page spread, four red stripes on a bright yellow background stretch across the paper like bloody marks and become a cipher for the Catalan flag. For Tapies, however, the strokes also become a symbol of resistance, supported by the word Visca, written sweepingly with a brush on the litho stone, which refers to the Catalans’ cry of protest ‘Visca Catalunya – Long Live Catalonia’, picking up on the heated, hopeful mood of the Catalans at the end of Franco’s military dictatorship.

Tàpies’ lithographs, bursting with power, are an instrument of political agitation, a way of personal rebellion in which the artist is fully aware of his will. Catalan identity is for him a concern in need of protection, a concern that must be defended. For the means of expression, he chooses lithography, a printing process, a reproduction process that allows him a very personal approach, but also imposes rules on him. It is quickly clear to the young people in the museum, looking at this work, that the artist is concerned here with something important, something that affects him personally, for which he is prepared to mobilise forces. The question about things that are important in life always opens up a lively discussion in the museum about personal power budgets and points to the many little challenges in life that sap strength or annoy. At the same time, the sources that provide strength and are important also come to mind. The contributions to the discussion are collected in groups, and handwritten thought clouds of the most diverse concepts emerge, such as Family, Friends, Laughing, Football, Boxing, Learning, Being ok, Respect, Parents, Siblings, Holidays, Sleeping, Culture, Love, Nature, Don’t forget your mother tongue, Helping out and so on.

3.

In the next step, the young people are asked to print or to stamp the terms they have previously collected, to produce their personal book out of it on the topics that seem important to them, that give them strength. You can observe that most of the terms previously written by hand are narrowed down to a few essential ones in the process of stamping or printing (Picture 3).

Printing seems to cause people to formally encircle themselves, to reconsider the thoughts they immediately conceive and to focus on what is essential. As in the example of Tàpies, the message narrows down to the clearest and most important, with the self at the centre and the technique of printing or stamping playing an essential role.

The technique thus influences the message and the process of printing favours the creation of something typical and something important. In the production of something universal lies the great opportunity of visualising ideas, of concretising ideas. Printing compels us to move from the particular to the general, even if it is a personal expression.

Writing by hand on the opposite enables direct personal expression in its immediacy. Thoughts are expressed in their spontaneity and individuality. A handwritten book, for example, is a ‘historical individual’ that evokes the person of the writer for all eternity. ‘A printed matter is [in contrast] a typical thing.’ Moreover, the immediate expression is virtually held up by the technique of printing, of forming a typography, for example. The technique is a kind of obstacle that forces one to consider what is to be expressed. If a word, a statement, for example, is to be printed by hand, many activities are required. Types must be set, the set type inserted into the press, ink and paper applied, the printing process carried out and checked. Even simpler processes such as stamping or roller and stencil printing force us to deal with the statement to be printed, because it is laboriously worked out. The technique influences the message, and the process of printing favours the creation of something overarching. In the work of art and museum education, these insights are a valuable asset. In the production of something universal lies the great opportunity of visualising ideas, of concretising ideas.

In another project from 2019, a series of postcards was created in cooperation with a group of girls and young women in Offenbach, which dealt with the topic of personal freedom on two project days. Which freedoms do they already have, which do they have to defend if necessary and which do they wish for themselves or their children. Corresponding statements could be filtered out of a wealth of oral and written suggestions, printed, stamped or typed. Copying was also done with a photocopier and the statements were pasted in public places in the city.

Words like ‘Parenting is work’ then drew attention to the problem of young single mothers to get a part-time apprenticeship. This statement we pinned on the wall of the job center in Offenbach to remind people of the fact,that working and motherhood are both important tasks for society and are not easily compatible. We also had demands like ‘I don’t want to be excluded’ or ‘I want to decide about my body myself’. In a final step, the photos of the statements were put up in a series of postcards.

In this format, too, the groups developed clarities about wishes they have for society and their lives through the process of printing or stamping and formulating them in public space. Here, too, the technology favoured the formulation of something typical in comparison to the previously created handwritten collection of ideas, personal values and ideas nevertheless manifest themselves in the decision for the comprehensive in printing. In printing, one comes close to oneself!

So printing makes an offer to express ideas and opinions and printing museums have the opportunity to just listen to them. I think this is a great chance to stay very close to contemporary ideas and to stay relevant in today‘s life of people in our societies, because we can support change. And as you might have seen, it is not important to get the techniques exactly right or have every little piece together, it is important to let people say something and to listen.

The digital space (Picture 4) also opens up wide possibilities to improve the communication situation between museums and society and to achieve real interaction, two-way communication, which is what we need. At the Klingspor Museum, for example, we have the problem that our archive material on the font designs of the Klingspor type foundry is repeatedly requested as scans, but we are then hardly connected to what happens with the materials in further use. In fact, there are several new typefaces already based on Klingspor fonts, such as Neue Kabel by Marc Schütz, Sig by Ethan Cohen or Archivschrift by Laura Brunner and Leonie Martin, and the archive material offers a wide range of possibilities for research and new design ideas, we just don’t know, how to keep in touch with. A cooperation with the neighbouring Hochschule für Gestaltung (University of Design) has resulted in an Institute for Type Design that deals almost exclusively with Klingspor typefaces. Two graduates, the mentioned Laura Brunner and Leonie Martin, developed the idea of a website that functions as a digital Klingspor Type Archive. At the moment we are in the final programming phase of this website, in early summer it will go online and it will fulfil several functions that will take us further in the means of our communication (Picture 5). On the one hand, relevant archive material will be digitally available and accessible, most of which will be copyright-free. So that’s again communication in one direction, from the museum to the people. On the other hand, there will also be the possibility to upload or link own projects in the Showcase and Research sections, so that we as a museum can also see what is being designed, said and written about Klingspor typefaces around the world.

5.

Little by little the website will grow with the material we put in and also with the contributions of other people who may look at the materials quite differently than we do. (A tattoo was made from a Klingspor ornament for example.) A pool of knowledge about type design, type history or new uses will build up and here too I look forward to learning from the resources outside of our bubble that will enrich us enourmesly.

We all have a lot to offer, but to make us relevant in the future I suggest we add another task to the canon of museums, and that is listening and engaging. Certainly we will lose knowledge about techniques, about processes in relation to printing, but we will also gain new knowledge and approaches to expression, because printing was in the first place designed to spread ideas and influence society through information. And that is something we can still rely on, but we need to use the resources, people in our societies can offer.

The Klingspor Museum is a small museum with a tiny team and I know, I’m referring to small and simple steps we are making, but I think it is at first more a change of mindset that seems important to me. And maybe you also share these impressions and have already larger ideas and experiences to include the wider society, I know there are also approaches in curating and collecting with other people, so I’m curious to hear your thoughts on the topic and we can of course discuss matters later on as well in a two-way communication.

For now I would like to thank you very much for listening to my thoughts and I would be happy to listen now to everyone else.