Over the years, within a network of interested collectors (both private and in museums) a kind of a three-way game has developed to moderate a specific Offenbach topic: Anton Würth and his copperplate engravings in correspondence with selected historical masters. The artist was kind enough to share his abilities and the process of his projects with Armin Kunz on the one hand and Stefan Soltek on the other. Kunz – together with his compagnon Carlo F. Schmid – is the moving force of C. G. Boerner (New York/Düsseldorf) one of the finest addresses for master prints throughout the different periods. Boerner was and is most engaged to launch its judgement of Würth’s skills and recommend them to both specialists in the art and techniques of engraving and to collectors. Stefan Soltek at the Klingspor Museum is very attached to the area within which the artist works and follows his activities closely, on occasion introducing some of the resulting works into the print collections of the Klingspor Museum and Haus der Stadtgeschichte in Offenbach. As both museums are members of AEPM, we are very pleased to offer our readers Armin Kunz’s text on the newest series of Anton Würth’s prints. Enjoy!

Printing as such is not an art, but an ideal of beauty might still appear after all

Armin Kunz on Anton Würth’s Essay on Runge

Starting in 2007 with two series of engravings that fashioned a dialogue with Robert Nanteuil (1623–1678), engraver to the Royal court of Louis XIV, Anton Würth (b. 1957) has closely studied the work of some of his ancestors in the medium of intaglio printmaking. The results of his close observations over recent years of early-modern ornament prints, Baroque garden books, and lastly the engravings of Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) help him to continually perfect his own burin work. The elegance of Nanteuil’s taille, the precision with which Dürer shapes forms through modulating lines, the astonishing richness of Schongauer’s blacks, or the flourishes of Baroque ornamentations all inform his artistic practice. The resulting works, however, remain free of any of the historicizing appropriation that can often be found in contemporary art. He does not, in the words of the critic Faye Hirsch, ’embrace historical styles from a position of efficacy or reaction. Indeed, looking closely at his enigmatic, paradoxical images, one might argue that, from his perch on what he devises as the razor-edge dividing abstraction and representation, uniqueness and repetition, decoration and content, Würth has arrived – via an unabashedly old-fashioned conveyance – at some of the fundamental issues of art in our post-modern age.’

- Morning

- Day

- Evening

- Night

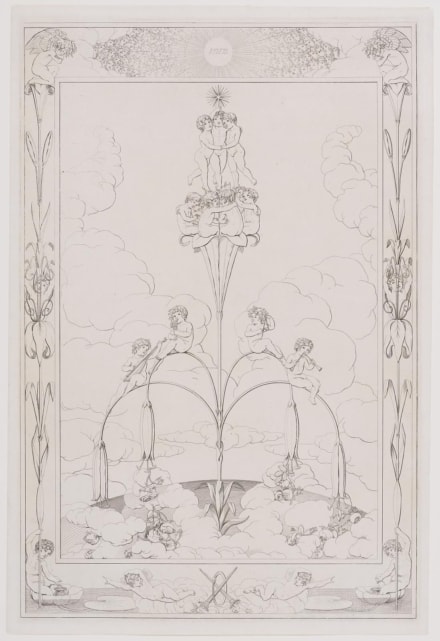

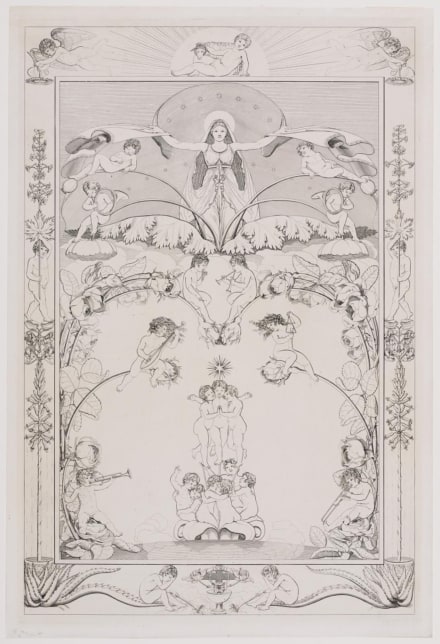

Würth’s latest dialogue has been with the German artist Philipp Otto Runge (1777–1810) and his monumental, albeit enigmatic, print cycle The Times of Day. In Runge, Anton recognized a kindred spirit. Both make art that resists being easily consumed. Furthermore, Runge’s reliance on ornamental forms resonated with his own concept of the Ornamental. For Würth, ornament is the perfect visual expression of the interesseloses Wohlgefallen (disinterested pleasure) that since Kant has defined the essence of beauty. The engraved line alone oscillates between meaning and being-for-itself, between referentiality and self-referentiality. It is the very place where the conventional unity of semiotic form and contents is called into question. Once this line is formed into an ornament, it is, in Würth’s own words, ‘voided of its referential potentiality and thrown back to its “being as is”. No reference is made to anything that exists beyond the binary relation of marked/non-marked; all that is shown is what can be seen.’

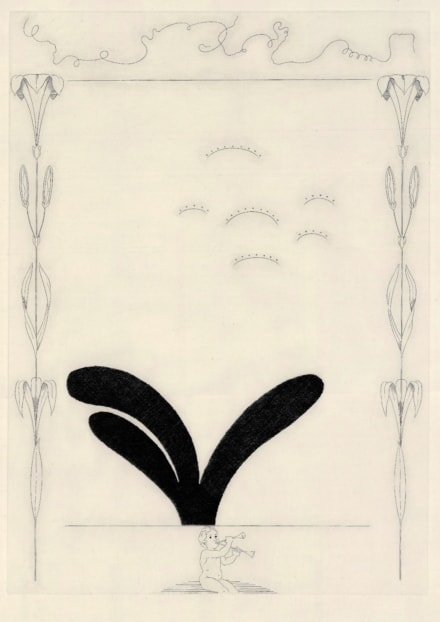

His Essay on Runge series adapts the old master’s dichotomy between frame and center. Yet whereas Runge remains recognizable in the framework of each of the four prints, the central images are entirely Würth’s own. The one exception here is the bold motif of a three-fingered plant that derives from David Hockney’s 1964 painting Man in shower in Beverly Hills (Tate Modern, London). Reminiscent of backlight silhouettes caused by the rising sun, the plant offered itself as metaphor for Morning, the first of the four prints, and enabled Würth to ultimately break away from the hold Runge’s imagery had over him. Only then was he able to organize the interior compositions in his very own visual language.

- Morning

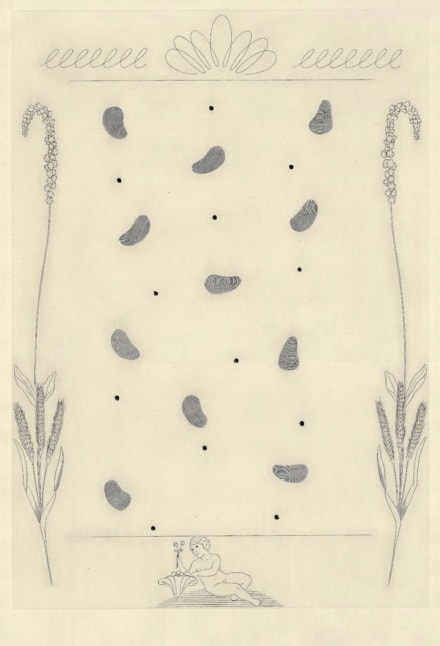

- Day

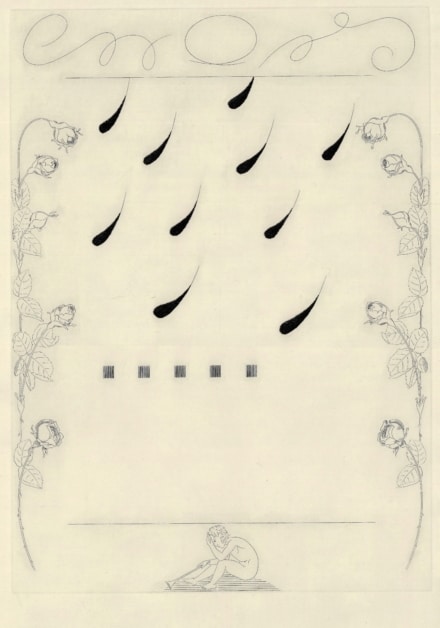

- Evening

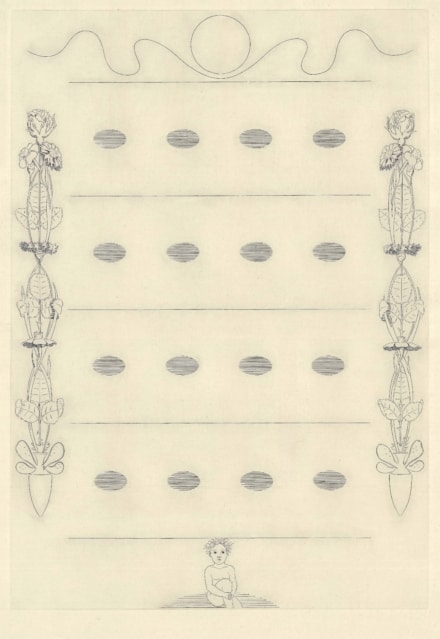

- Night

Runge’s pared-down linework is echoed in the whimsy of Würth’s prints, a lightness that hides not only the intellectual complexity of his work and but also the intensive research, meticulous planning, and painstaking execution that goes into them. In recent years, Würth’s choice of paper has also begun to play an increasingly larger role, most notably after his encounter with the Japanese gampi paper that Rembrandt’s often used for his later prints. The Essay on Runge engravings are printed on a subtly ivory-toned 8 monme Echizen Ganpi which the artist, who makes regular trips to Japan, usually brings back from Tokyo himself.

The finished prints are anything but flashy. The truth is that it is even virtually impossible to do them justice in reproduction. What they require, instead, is the beholder’s patient attention in front of the original. At its best, then, Würth’s work proves that out of the sweaty, smudgy, and inky aspects of printmaking an ideal of beauty might still appear after all. Now, at a time when we all have had to give up the ongoing acceleration of our lives, this hope has actually gained an added relevance, if not an urgency. Perhaps the Entschleunigung (deacceleration) that the ‘new now’ has imposed on us could be the one good thing to hold on to once the current crisis is finally over. What better time than now, then, to start looking more closely? As Faye Hirsch had observed some years ago when reviewing another print cycle by the artist: ‘The time he spends on each of his projects seems generously to be transmitted to us viewers caught in the rush of technology and spectacle, and we luxuriate in the pause he invariably offers.’